Gaming Made Me, #4: John Walkthrough

I go last because I'm ugliest. That's just the way it works at RPS. So after Jim, Alec, and Kieron, it's my turn to try to pick a collection of games that have defined me as a gamer, and indeed defined me as a person. It's a daunting task.

Ingrid's Back!

In truth, I couldn't tell you a single thing that happens in this Level 9 text adventure. I know it stars a gnome, and her name is Ingrid, and it's the sequel to Gnome Ranger about which I know even less. I played it on the Spectrum 48K when I was 10 years old, but crucially, and here's why it's the first game in a list of my most significant games, I played it before it was released.

If you were to have visited my house when I was ten, in 1988, you'd have had a good chance at accurately predicting my future career. Sat next to my dad (who is a dentist in work hours), playtesting pre-release text adventures. There's a good chance I might have even written something about it for the Adventure Probe zine (to steal Kieron's gag: the other AP), to which my father regularly contributed, and certainly the first place I had any games writing published. I think we were playtesting it for bugs as a favour for someone my dad knew at Level 9, but I might be making that part up. As you can tell, the game itself isn't the important part here. It happens to be a rather good one, scoring some pretty decent reviews at the time. But for me, it's more a snapshot of my past that seemed to be programming me for the future.

The strange thing is, if you'd visited my house three or four years later you'd never have been able to draw the same conclusions. My teenage years were spent playing endless games on many machines, still adoring the pursuit. But my career was to be in microbiological sciences. Of course, if I'd spent more time doing homework and less time playing games, perhaps that might have happened. It wasn't to be, and a passion for writing and a love of games brought me here. But I don't think for a second I'd be a hardcore story gamer, and certainly not a games critic, were it not for those times sat next to my dad, playing through games we'd received before publication. And whenever I think about that time, it's Ingrid's Back that comes straight to mind. You know, apart from what happened in it.

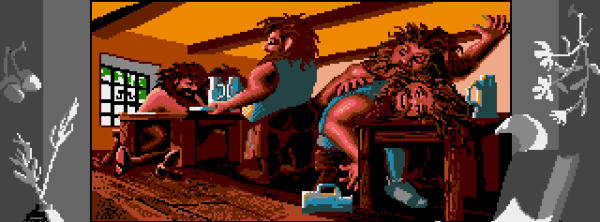

Dungeon Master

I'm going to return to my dad again here. Clearly he has been an enormous influence on my gaming habits, having bought a ZX81 in the early 80s, and then kept up with non-console machines ever since. We went off on different paths once the 3D dungeon crawlers spawned FPSs, and adventure games became point-and-click, him staying with RPGs. But long before this, in 1987, came Dungeon Master.

I'm tempted to tell stories of playing Buggy Boy with my sister, or Bubble Bobble in co-op with my friend Alistair (that story told in part here), but the Atari ST story that defines me most has to be watching my father beat the level 13 boss in Dungeon Master. So this would be around 1987, I'd have been 9 or 10. At this time my dad's ST was set up on the breakfast bar in the kitchen, where he would spend his evenings hunched over the machine in the corner of the room, the kitchen door banging into him when opened too quickly. I would love to pull up a stool next to him and watch him playing games, inevitably eventually asking him if I could have a go, ruining whatever progress he was making in whatever he was playing.

You can read about all the many firsts Dungeon Master achieved in its Wikipedia entry. But it's safe to say it was a landmark game, played in real time, in an approximation of 3D, using mouse and keyboard controls. It was a new experience for anyone who played it, the safety of turn-based combat taken away from you, enemies able to attack when they chose, even if you weren't done getting your potion ready. I remember playing my own saves of the game (never getting beyond the fourth or fifth floor, I suspect), and the thrill of mixing spells in flasks, successfully creating fireballs from their component parts, preparing for a battle ahead. It was a game that forced you into seeking sanctuary, no longer able to rely on the world patiently pausing while you sorted yourself out. A room with a closable door, ideally with a couple of empty chests for storing your excess inventory, was a haven, a safeground to which you could retreat, hide, recover, and prepare. This sense of safety only emphasised the sense of danger outside. The threat of an enemy, chasing you down corridors (admittedly in leaps across tiles), hurting your party of four when it got near, often became terrifying. I remember fumbling at the controls, throwing bottles of water at skeletons instead of poison, fluffing things up so badly that members of my team would have their portraits hideously replaced with messes of bones and a skull. Characters with names and skills and possessions and armour. People I'd chosen from that peculiar gallery at the start of the game, clicking on paintings of their faces to have them join my gang. Dungeon Master was a game of fear and recovery, danger and relief. It frightened me greatly. But not my dad. My big, strong dad.

Until level 13. Forgive me if I'm getting these numbers wrong, but from memory the titular dungeon was fourteen storeys deep. On the very bottom floor the eponymous Dungeon Master lived, the final scene of the game. But on the floor above him was a giant red dragon, an enormous enemy that required one hell of a fight. I was there the day my dad first encountered the dragon, sat next to him at the kitchen counter, watching him expertly play. Watching his hand shaking on the mouse.

Shaking. His whole hand trembling with genuine fear at the fight. My dad's big, strong hand.

Day Of The Tentacle

In these exciting times of LucasArts appearing to rise from the ashes of Star Wars tedium, with remakes of Monkey Island, and selections from their back catalogue appearing on Steam, there's one cry coming out from my soul: WHAT ABOUT DAY OF THE TENTACLE?!

I'm often very surprised by how many other games are mentioned before it when people list their favourite adventures. Monkey Island 1 or 2, Fate Of Atlantis, Sam & Max, and most of all, Grim Fandango. But for me it's Day Of The Tentacle first and foremost, on a tall mountain, waving a giant flag. Alec has previously eulogised the Sam & Max opening sequence (as wonderful as they are), but I don't think it comes close to DOTT's ludicrously well written, animated and performed intro. Indulge me a moment:

DOTT understood what being a cartoon was all about. It was an adventure game first, but it was a cartoon a very close second. As such, it was able to embrace cartoon logic into its already astonishingly clever time-travel story. David Grossman and Tim Schafer writing and directing characters created by Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick (DOTT was of course a sequel to Maniac Mansion) - it was the dream team.

And for me, it was the game that just bellowed everything I could ever ask for (but for pathos, arguably, but of course that would have been wildly out of place here). I want it to be fantastically well written, I want the puzzles to be both obscure and rewarding, and most of all, I want it to be funny. I've spent my career lamenting gaming's failure to achieve these three things.

I especially remember buying it. There was a shop in Guildford, upstairs in the White Lion Walk shopping centre, called Ultima. It was run - and I promise this is true - by a short, fat, moustachioed Italian man called Mario, who ran the business with his brother. Endless amusement. Also working there was a tall, astonishingly morose guy called Adam - someone I used to drive mad by visiting every Saturday and talking at about games, his laconic, cynical responses unable to puncture my enthusiasm. (Oddly I ended up working with him at an EB years later, and he hadn't changed at all.) So, one Saturday I went in the yellow shop and saw the Day Of The Tentacle boxes. Of course I'd read that a new LucasArts adventure was on the way, but what I didn't know was that it would be packed in a huge, triangular box. (Thanks to Petërkopf for finding the pic of it.) What a moment.

I think DOTT was the first time I found myself wanting to quote a game. I'd been loving wonderful Sierra and LucasArts games for years previously, but nothing quite sang to me like this. I would do impressions of the characters (I still do as I play it now). I knew the solutions to all the puzzles, but the scenes were so great it was worth playing through them again. It made me believe in gaming as a medium for hilarity.

I think what DOTT has done for me more than anything else is give me a sense of expectations that I deserve. Comedy games may be 99% terrible, but because of Day Of The Tentacle, I remember that there's no excuse for it, there's no room for accepting rubbish out of desperation for something. A bar was set in 1993, and I refuse to let it get me down that the only person who's met it since has been the guy who put it there in the first place, Schafer. It keeps me honest. It makes sure I remember what others should be doing, and acts as a place to point toward when they're not. Of all the story-led games in the world, I think it's the only one I could play again and again and again.

Lemmings

Perhaps this is a bit of an obvious choice. If you draw a graph of puzzle gaming, there's one bloody great spike at Lemmings that makes it rather stand out. But if you can tolerate my getting so ambiguously anecdotal again, it was the moment as much as the majesty of the game.

Here's the ambiguous part. (I'd phone my parents to get some clarity on these stories were they not out the country this week.) My dad was visiting a friend of his, who was another 40-something gamer. I had gone along, and circumstances were such that when the two of them went off to have a meeting about something or other, I was left entertained in front of a PC running a copy of Lemmings. I vaguely remember that the room with the PC was in a separate building from this (obviously pretty well-off) guy's main house. I also strongly remember that playing in the background was an album by Chris Rea. I'm fairly convinced it was Road To Hell, although it could well have been Auberge, since that came out the year before, in 1991. I'd have been thirteen by this point.

I've no idea how long I was left in that room. What I do know is that I was utterly content. I had this remarkable, beautiful, almost-perfect puzzle game to play, featuring the gorgeous animations of the floppy-haired blue/green suicidal creatures, guiding them to safety. This was a game that utterly, utterly worked. There's a reason why every single World Of Goo review called back to Lemmings - it was the last time a game had felt so engrossing, so joyful, and just so right. It was like I'd been left with something so special I shouldn't have been trusted with it.

It was like I'd walked into a magical house, the sort of place that had to be specially built to contain something as enjoyable as Lemmings. I think I assumed it wouldn't be possible to play it again once I left. I don't think I ever loved it as much as I did that time, as it happens. Although I do specifically remember the almost equally magical joy of getting Holiday Lemmings for free on the front of a magazine the next year, and not being able to understand how something so wonderful was just there, for free, for me to enjoy. I don't think I will ever play Lemmings again. It simply cannot be as good as I remember, and certainly the twenty year old graphics won't do it justice. I'd like to keep it how it exists in my mind just now, inside that specially created room, with Chris Rea crooning mournfully in the background.

The Longest Journey

If anyone were taking bets about which games I'd include in this collection, no one would have accepted money for the appearance of The Longest Journey. I've written so much about it, and uniquely, written very personally about it on many occasions. Some people have the album they heard that changed their lives. Others credit a book with shaking up their perspective on the world. For me it was a point and click adventure with some of the worst puzzles you'll ever find.

The timing was interesting. Released in late 1999, this was around the same time I was starting out as a games critic, getting my first work in PC Gamer. I'm sure I must have read previews of it, enough to be interested in it, and certainly enough to know to ignore Steve Brown's daft review of it in PCG ish 83. (Love you Steve, obviously. But I'll also never forgive you for that.) I'd been writing occasionally in the mag for about four issues by this point, and I remember my fury as I read the one page of banging on about the game featuring a blue penis and swear words. It became my mission to mention the game in every review I wrote (handily PC Gamer had a bit at the bottom of each review at the time that let you recommend two other games that were similar - no matter how dissimilar, The Longest Journey got a mention, along with a dig at how wrong the original 79% review was).

But more importantly, I was 22. I was freshly an adult, seeking my first proper job, and venturing into real life. And at that moment, here I had a game about 18 year old April Ryan, finishing college, and venturing into real life. Except of course her real life became decidedly unreal. I was malleable, changing, finding my philosophies (Deus Ex would of course come along a year later and work on that too), and The Longest Journey contained one message that transformed me.

To play the game now, you've got a peculiar mix of beautiful painted backdrops and fuzzy, pixellated messes for characters. You'll find some completely atrocious puzzles (none more so than the policeman on toilet/glass eye/medication puzzle that doesn't work in 124 different ways). You'll also find a script written by someone who'd been watching an awful lot of Buffy The Vampire Slayer. But here's the important bit: it was someone who not only was clearly influenced by Whedon's writing, but was as good at it as Whedon.

I'm obviously horribly underselling the game in some ways. But I'm trying to maintain some level of reality here too. It wasn't perfect. But it was human. So incredibly human in a way I'm not sure any other game has come close to. You may have been playing a stroppy late-teenage girl who was friends with a talking crow... in the future. But you were playing a real person, interacting with other real people, in real ways, despite the hover-cars, alternative realities, and rubber-duck-themed puzzles. April's stroppiness was a facet of her complex character - a person also capable of enthusiasm, love, fury, fear, joy, optimism and a wry, sneaky humour. She was someone with whom I engaged very strongly.

Which is crucial to the impact TLJ had on me. (I almost resent writing this warning, but the following will spoil the end of the game.) April Ryan isn't the hero of The Longest Journey. She isn't the saviour of the worlds. She doesn't restore the balance between Stark and Arcadia. She may be the daughter of the white dragon, or she may not. She may have some deep significance to the universe, but I've a sneaking suspicion it's no more significance than anyone else alive. She plays her part, she affects the world/s around her, she makes important differences in people's lives. She has an important role in the processes that lead toward the restoration of the Balance. But she isn't the new nudie blue figure who will protect the lives of billions of people. She thinks she's going to be, she wrestles with the fear of such a part to play, but at that final moment, that's not her job. She isn't the hero of the story.

I'd identified with her in a romantic desire to see myself as that sassy, witty person too. And because who doesn't want to be the hero of the story? But then it turned out she wasn't, and neither was I. It was this that widened my eyes: April was heroic. April was significant. April saved. April made a difference. But she wasn't the hero, she wasn't the saviour.

Our understanding of the part we're supposed to play in the world is perhaps something we struggle with our entire lives. April was shown a glimpse of something enormous that would give her life definition and meaning. It wasn't hers, it didn't turn out to be about her, and as Dreamfall so stunningly goes on to portray, facing this destroyed her. But I realised this wasn't a message of destruction or failure. It was about the reality of how important each person is, and the potential everyone has to make a significant difference to the world, but without the world ever noticing them. It's about matching the desire to see change with the humility to realise no one will know to care that you did.

Balance wouldn't have been restored without someone playing the part April filled. April's actions made a difference, even if they didn't culminate with her as the glowing figure for all to see and admire. Someone else could have done her job instead of her, but it was April who did it. I realised that's my role too. Anyone's role. To seek out chances to make a difference, to fill the role that anyone else could, but to be the person who did.