Hitman and the joy of killing your boss

Zero hour contracts

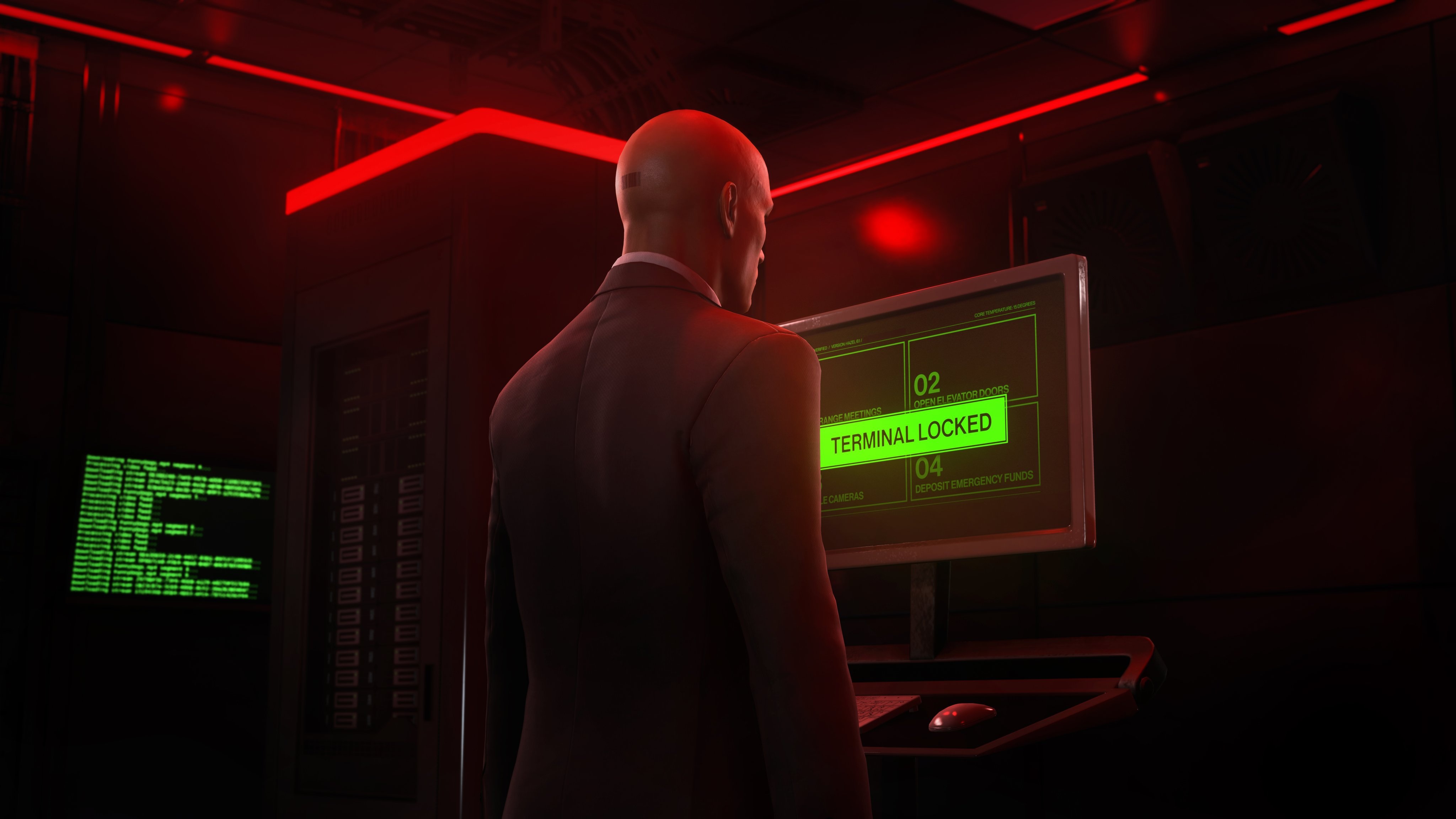

I used to see Agent 47 as a sociopath. “A blank slate”. The ideal state for a video game protagonist. Hitman puts us right in his polished black shoes. A gulf of meaning into which we can project ourselves. 47 has a contract, we have an objective. Our goals are aligned, even if we can’t quite get behind the brutality of it all. Between entrance and exfiltration stretches out a space littered with pistols and piano wire, rat poison and rubber duck bombs, faulty wires and water pumps. What kind of person 47 is, how the cogs behind that barcode turn, is our shout.

If we want, we can turn his penchant for creative violence into a fine art. We can slink through these cities and rooftops without a trace, or leave a snaking trail of corpses. Electrified waiters. Screwdriver-skewered security guards. A chef in a toilet for some reason, why not? But that’s not my 47. My 47 is an avenging spirit. A manifestation of working class anger. A proletariat superhero. For me, Hitman isn’t just a game about killing. It’s a game about killing your boss.

There’s a great piece of writing by James Patton where he talks about the stealth genre in relation to 1941 film noir The Maltese Falcon, in which the author says: “A setting infiltrated during a stealth game ... constitutes its own subculture”. Hitman, with its tangly spiderwebs of social interactions and strictly enforced social codes, always reminds me of Patton’s words.

When 47 intrudes upon a Sapienza mansion or a resort high in the mountains of Hokkaido, the culture he infiltrates is one formed from the daily rituals of the women and men who work there. He disguises himself among those lower than his target on the societal hierarchy, gaining access to his targets by exploiting the assumption that their employees pose no threat. That they would never dare bite the hand that feeds.

Game designers sometimes talk about ‘The Magic Circle’ - the new reality we enter when we play a game, shaped by the unspoken contracts of play. This circle prevents us from “holding a grudge” against our opponents once the game is over, says Nathan Hook in an essay called ‘Circles and Frames’. Whether it’s blood spilled in the boxing ring, or beating family members to death with their own limbs over a game of Monopoly, conflict dissipates as soon as the game is over. The transgressions that took place within the circle, forgotten. I think the sliding double doors that delineate street from workspace function in the same way.

When a boss or manager belittles us, demeans us, or otherwise treats us like disposable human garbage, they’re hiding behind the socially constructed equivalent of a DM’s cardboard screen. A flimsy ruleset that spells out how the performative role play of the office, factory, or restaurant is meant to function. If a stranger clicks their fingers and barks orders at you in the street, no-one’s going to blame you for bowling your twenty piece McNugget box at their forehead. If your shift manager at McDonald’s does it, well, that’s just the rules of the game, right? Once you put on the uniform you’ve surrendered agency in the same way a dungeoneering elf surrenders health insurance. Your manager isn’t being a dick to you, they’re being a dick to you at work. In gaming parlance, they’re being a dick to your avatar.

The advantage our bosses have, of course, is while they can kill off our characters any time they like and replace them easily, we need to uphold this fiction to survive. We need to keep reassuring the emperor that we see and respect his +1 new clothes of illusion, even if we can see his shrivelled danglies poking through the edges. 47, however, is only required to traverse this hierarchical network for as long as the contract takes him.

If 47 acts out a waiter's job for hours, waiting for the perfect moment to strike at his target, and emulating their expertise and mannerisms, why wouldn’t he start to feel some of their frustrations too?

When we play as 47 in disguise, we roleplay as a roleplayer. This role-ception (not to be confused with Rolo-ception, the delicious act of discovering mini Rolos inside regular size Rolos) is where 47’s moral centre is located. Like a bald, murderous Kirby, when the hitman disguises himself, he absorbs a part of this new identity. We might not be able to relate to 47 as an individual, but most of us can see ourselves in the exploited workers of media moguls or narcissistic fashion designers.

As we watch waiter 47 turn practically invisible when he stops to mix drinks in a crowded bar, it seems like the game is asking us to assume that he’s such a good chameleon that blending in is effortless. But we’re really being shown something else.

“People do tend to see uniforms, not faces” the Hitman’s handler acquiesces during the tutorial mission, as the killer disguises himself as a mechanic. Alienated, faceless, powerless, and replaceable, these women and men were always going to be the perfect disguise. As far as their employers are concerned, they were invisible in the first place.

The workers themselves might never be able to take revenge on those who exploit them. Thanks to Hitman, though, the last thing they see could still be a chef’s whites, or a security guard’s jacket, or a waiter’s tux.

He might not be as iconic as Solid Snake, as instantly recognisable as Sonic, or as effortlessly fuckable as Waluigi, but in an industry where writers can be sacked just for calling fans out on their condescension, and where the need for unionisation becomes clearer everyday, maybe 47, in all his boss-killing glory, is the hero we need right now?

Welcome to the resistance, 47. Just, uh, try not to leave any rubber ducks around, okay?